Spin Hall Effect: Mechanism and Applications

Introduction

The Hall effect, traditionally associated with the generation of a voltage perpendicular to an electric current in a magnetic field, has evolved to encompass phenomena that involve the manipulation of electron spins. One such phenomenon is the Spin Hall Effect (SHE), which plays a crucial role in the field of spintronics. Unlike the conventional Hall effect, the Spin Hall Effect does not require an external magnetic field to produce spin currents, making it a pivotal mechanism for developing next-generation electronic devices.

Mechanism of the Spin Hall Effect

The Spin Hall Effect arises from the intrinsic properties of materials and the spin-orbit coupling present within them. When an electric current flows through a non-magnetic conductor, spin-orbit interactions cause electrons with opposite spins to deflect in opposite directions. This separation of spins leads to the accumulation of spin-up electrons on one side of the material and spin-down electrons on the opposite side, resulting in a transverse spin current.

Key Factors Influencing SHE

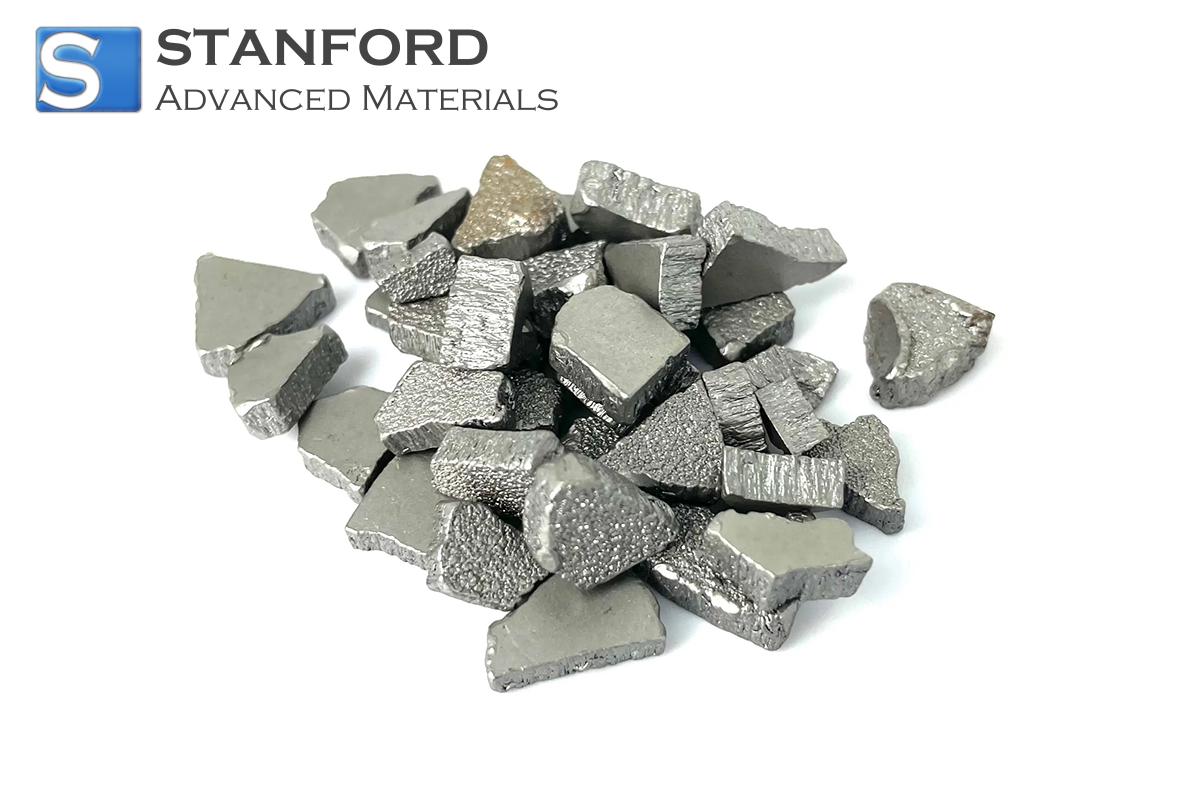

- Material Composition: Heavy metals like platinum and tungsten exhibit strong spin-orbit coupling, enhancing the SHE.

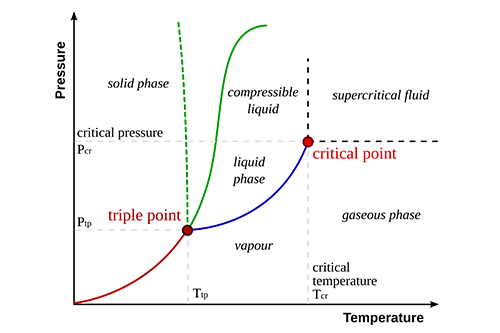

- Temperature: Lower temperatures can reduce phonon scattering, increasing spin current efficiency.

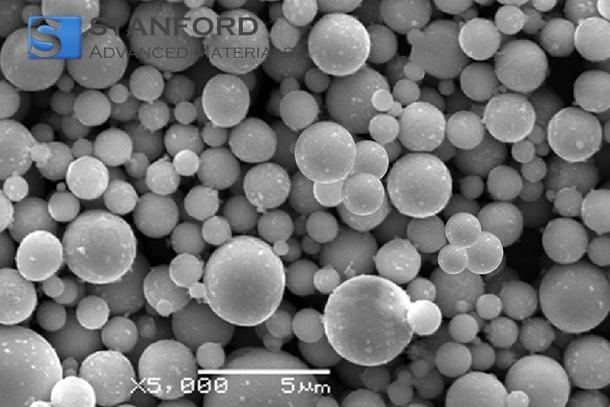

- Layer Thickness: The thickness of the conducting layer affects the magnitude of the spin current generated.

Applications of the Spin Hall Effect

The ability to generate and control spin currents without external magnetic fields opens up numerous applications in technology:

Spintronic Devices

Spintronics leverages the spin of electrons in addition to their charge for information processing. SHE enables the creation of spin-based transistors and memory devices with higher speed and lower power consumption compared to traditional electronics.

Magnetic Memory

The Spin Hall Effect facilitates the manipulation of magnetic domains in memory devices, leading to the development of more efficient and compact magnetic random-access memory (MRAM).

Quantum Computing

SHE contributes to the stabilization and control of qubits in quantum computers, enhancing their coherence times and operational fidelity.

Spin Hall Effect Parameters

|

Parameter |

Description |

Typical Values |

|

Spin Hall Angle |

Efficiency of charge to spin current conversion |

0.1 - 0.2 |

|

Resistivity |

Electrical resistivity of the material |

10 - 100 μΩ·cm |

|

Spin Diffusion Length |

Distance over which spin current persists |

1 - 10 nm |

|

Critical Current Density |

Current density required for spin current generation |

10^6 - 10^8 A/m² |

|

Temperature Range |

Operational temperature range for SHE devices |

4 K - 300 K |

For more information, please check Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Spin Hall Effect?

The Spin Hall Effect is a phenomenon where an electric current in a conductor leads to a perpendicular spin current due to spin-orbit coupling, resulting in the separation of electron spins.

How does the Spin Hall Effect differ from the traditional Hall effect?

Unlike the traditional Hall effect, which requires an external magnetic field to generate a voltage perpendicular to the current, the Spin Hall Effect relies on intrinsic spin-orbit interactions without the need for an external magnetic field.

What materials are best suited for observing the Spin Hall Effect?

Materials with strong spin-orbit coupling, such as platinum, tungsten, and certain topological insulators, are ideal for observing a pronounced Spin Hall Effect.

What are the main applications of the Spin Hall Effect?

The Spin Hall Effect is primarily used in spintronic devices, magnetic memory technologies, and is being explored for applications in quantum computing.

What challenges need to be addressed for the widespread use of Spin Hall Effect-based devices?

Key challenges include finding materials with optimal properties, developing scalable manufacturing processes, and integrating spintronic components with existing electronic systems.