How to Choose the Right Optical Window Sheet for Your Project?

Introduction

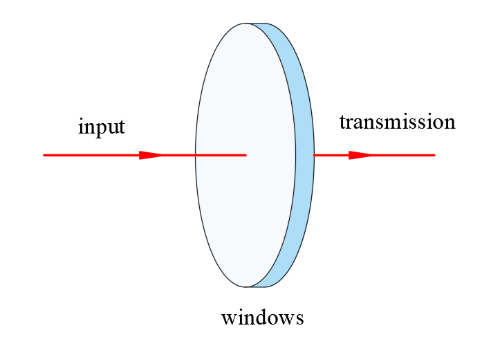

An optical window piece is an optical element that transmits light and is usually made of transparent materials such as glass, quartz, and ordinary optical glass. Its main role is to protect the components inside the equipment and transmit optical signals. In optical equipment, optical windows are often used to protect lenses, filters, optical fibers, and other components from external environmental pollution and physical damage, such as dust, rain, oxidation, and so on. In addition, optical windows can also adjust the luminous flux and spectrum, to adapt to the needs of different occasions, and to control and adjust the direction and angle of incidence of the light beam.

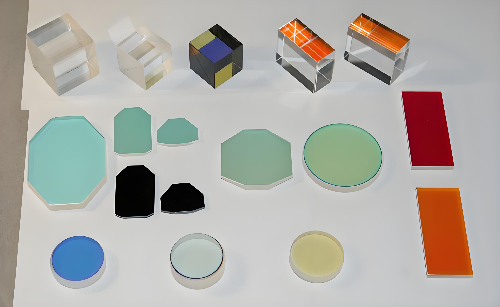

Fig.1 Different Optical Window Sheets

Different application scenarios place almost contradictory demands on optical window sheets - to maintain excellent optical transmittance while withstanding extreme environments. In spacecraft, it must withstand cosmic rays and drastic temperature differences; in deep-sea probes, it needs to withstand ultra-high water pressure and salt spray corrosion; and in medical endoscopes, it is necessary to ensure biosafety while realizing accurate imaging. This balance of multi-dimensional performance requirements makes material selection the primary issue in the design of optical window sheets, and scientists control the crystal structure, coating process, and chemical stability of the materials so that each piece of the “Guardian of Transparency” can be perfectly adapted to the unique challenges of its application scenarios.

Specifically, high-energy lasers require sapphire windows that can withstand high temperatures and radiation. Deep-sea detectors rely on blue sapphire glass for its pressure and corrosion resistance, while medical endoscopes utilize calcium fluoride crystals for their excellent biocompatibility. From capturing starlight in space telescopes to analyzing cellular structures in microscopes, and from solar panels to infrared sensors, the material science and functional design of optical window sheets are intrinsically linked to the precision, stability, and longevity of modern optical equipment.

Fig. 2 Principle of Optical Windows

Factors to Consider When Choosing Optical Window Sheets

Material Type

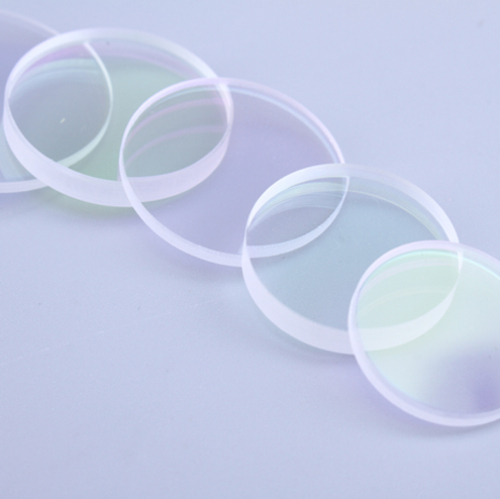

The choice of material for optical window sheets requires a combination of optical performance, environmental resistance, mechanical strength, and cost-effectiveness. Optical glass (e.g. BK7, fused silica) is the preferred choice for general-purpose scenarios due to its high transmittance (covering the visible to near-infrared wavelength bands) and affordability, but its temperature resistance (typically <500°C) and impact resistance are limited. Quartz glass achieves broad-spectrum UV-IR transmission through ultra-high-purity silica, and its high-temperature resistance (>1000°C) and thermal shock resistance make it suitable for extreme scenarios such as high-energy lasers and spacecraft observation windows. Sapphire (monocrystalline alumina) stands out for its Mohs hardness (grade 9), which is second only to diamond, and its ability to transmit light from the UV to the mid-infrared (0.15-5.5 μm), which is commonly used in deep-sea probes, armored optics, and high-abrasion environments. However, its high refractive index needs to be optimized by coating to minimize reflective losses. Engineering plastics (e.g. PC, PMMA) are irreplaceable in lightweight demand scenarios such as drone lenses and wearable devices due to their lightweight, impact-resistant, and injection-moldable advantages, but their temperature resistance (typically <120°C) and chemical resistance limit high-end applications. Special scenarios also require customized materials: for example, calcium fluoride crystals dominate medical endoscopes due to their biocompatibility and mid-infrared transmittance properties, while zinc selenide is dedicated to the long-wave infrared window of CO₂ laser systems. The essence of material selection is to match the core requirements - sacrificing mechanical strength in the pursuit of extreme light transmission, and balancing cost with environmental resistance - and modern coating technologies are pushing the boundaries of material performance.

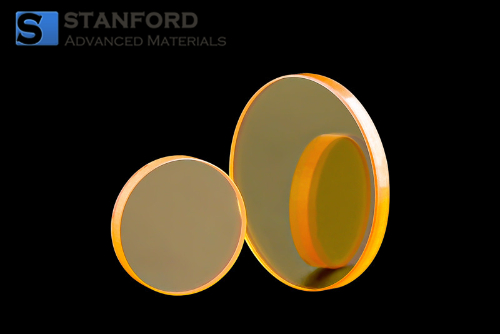

Fig. 3 Optical Glass with High Light Transmission

Thickness

The thickness of an optical window sheet is a key variable in the force-optical coupling properties of a material. In the mechanical strength dimension, thickness follows the thin-plate deflection equation in the mechanics of materials (δ ∝ P-L³/(E-t³)), and flexural strength is inversely proportional to the cube of the thickness, which means that a 25% increase in thickness improves deformation resistance by about 95%, but also results in a linear increase in weight. In the optical performance dimension, the thickness directly affects the optical travel length - when the window sheet thickness exceeds λ/(2Δn) (λ is the wavelength, Δn is the refractive index inhomogeneity), wavefront aberrations may be triggered, especially in high-power laser systems, where excessive thickness exacerbates the thermal lensing effect (the thermal focus equation, f ∝ κ-t/(α-P). (where κ is the thermal conductivity, α is the absorption coefficient, and P is the power). Transmittance, on the other hand, shows a non-linear relationship: according to the Beer-Lambert law, transmittance T = (1-R)²-e^(-αt) (R is the surface reflectance), and an increase in thickness amplifies the effect of the material's intrinsic absorption (the α term), e.g., the transmittance of a 5 mm thick fused silica in the ultraviolet (UV) band (200 nm) decreases by as much as 40% compared to a 1 mm thickness. Therefore, thickness optimization is essentially a Pareto optimal solution between compressive strength, aberration control, and light transmission efficiency.

Fig. 4 Quartz Window Sheets of Different Thicknesses

In extreme pressure scenarios (such as underwater 5000 meters deep submersible), the window sheet needs to meet the compressive strength formula P_collapse = K-E/(1-ν²)-(t/D)² (K is the shape factor, ν is Poisson's ratio, D is the diameter), usually using sapphire monocrystalline with a thickness of up to 8-15mm, and its compressive strength of 3.2GPa with a high thickness design to withstand 60MPa Hydrostatic pressure. While the standard optical system (such as microscope objective lens protection window) follows the principle of thinning, the use of 1-3mm thickness of BK7 optical glass, not only to meet the requirements of λ/4 surface flatness (PV value <0.5μm), but also to control the weight of the system load within 0.5%. For high-power CO₂ lasers (wavelength 10.6 μm), 0.5-1 mm thick zinc selenide windows become standard, a thickness that both controls the thermally induced focus shift to within 10% of the Rayleigh length (Z_R = πω₀²/λ) and guarantees >99% transmission (achieved by 1/4 wavelength anti-reflective coatings). In aerospace, thickness selection also takes vibrational modes into account: fused silica windows for typical satellite optical payloads are 2mm thick so that their first-order resonance frequency avoids the broadband 20-2000Hz vibration band of rocket launches. This precise thickness customization reflects cross-scale design intelligence from material intrinsic properties to system-level engineering.

Optical Properties

The transmittance, absorbance, and reflectance of an optical window sheet constitute the “golden triangle” of its optical performance, which together determine the transmission efficiency of the optical signal and the system signal-to-noise ratio. According to Bill Lambert's law, transmittance T = (1-R)2e-αtT = (1-R)2e-αt (RR for the reflectivity, αα for the absorption coefficient, tt for the thickness), when the ultraviolet band (200-400nm) need to be> 90% transmittance, fused silica (α<0.1 cm-¹ @200nm) and calcium fluoride become the preferred choice, while ordinary optical glass will be eliminated in this band due to absorption peaks caused by ferrous ion impurities (α>1 cm-¹). For the infrared window (3-12 μm), zinc selenide maintains a low absorption of α<0.02 cm-¹ in the longwave infrared (8-12 μm), while germanium has a superior transmittance (>99% @10.6 μm) but its temperature-sensitive absorption coefficient (α grows exponentially with temperature) requires the use of thermoelectric cooling.

In the field of UV protection (e.g. UV lithography), fused silica substrates are used with MgF₂ anti-reflective coating (reflectivity <0.5% @193nm), while the hydroxyl content is strictly controlled (<1ppm) to suppress the absorption band at 248nm. Visible windows (e.g. camera lenses) are often made of BK7 glass (transmittance >92% @400-700nm) combined with a broadband AR coating (reflectivity <0.3%), and its absorbance is maintained at <0.1% by controlling the Ce³+ impurity concentration. For the infrared thermal imaging system, the materials are precisely selected according to the working band: silicon wafer is used for short-wave infrared (SWIR, 1-3 μm) (transmittance >50%), sapphire is used for medium-wave infrared (MWIR, 3-5 μm) (special polishing is required to make the surface roughness <5 nm to reduce scattering loss), and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) grown Zinc Sulfide (ZnS) is standard for the long-wave infrared (LWIR, 8-14 μm). Zinc Sulfide (ZnS). For full-spectrum systems (e.g., spectrophotometers), magnesium fluoride (UV region), fused silica (visible region), and barium fluoride (IR region) are combined into a composite window by a multilayer stacking technique, with the thicknesses of the layers optically matched according to d=λ/(4n)d=λ/(4n).

Table 1 Optical Window Performance Core Triad and Wavelength Adaptation

Wavelength Range | Selected Material | Transmittance Threshold | Absorption Control Points | Coating Solutions |

Ultraviolet(200-400nm) | Fused Silica | >90%@200nm | Hydroxyl Content <5ppm | MgF2 monolayer film |

Visible Light(400-700nm) | Bk7Glass | >92%@546nm | Fe³+ Content <50ppm | Broadband AR film |

Infrared (3-12μm) | Cvd-Zns | >70%@10μm | Lattice Defect Density <1e4/Cm² | Diamond Film |

Optical Properties and Mechanical Strength

Optimization of optical window sheet performance is a multi-physical field coupled precision engineering, the core of which begins with the optical properties and the depth of the intrinsic parameters of the material binding - transmittance, absorptivity and reflectance of the composition of the “triangle of optical energy” directly defines the system's signal-to-noise ratio boundaries. In UV lithography, fused silica becomes the cornerstone of the EUV optical path by its >99% transmittance at 193nm (α<0.1cm-¹) and reflectance reduced to 0.2% by MgF₂ coating; while the infrared thermal imaging system relies on zinc selenide's intrinsic transmittance of >70% in the 8-12μm band, and surface reflection loss suppressed to <0.5μm by diamond film coating. The surface reflection loss is suppressed to <0.5% by diamond coating. Surface quality, as the first interface for optical energy transfer, shapes system performance with nanometer precision: laser gyroscope windows require λ/20 surface flatness (PV <15nm) to maintain <0.001λ wavefront aberration, and class 0 scratch-controlled surfaces by the MIL-PRF-13830B standard enable high-energy laser systems to exceed the damage threshold of 50J/cm²; The sapphire window is magnetorheological polished to 0.3nm RMS roughness, and with the ion beam deposited diamond-like (DLC) coating, it achieves >10⁹ friction cycles of scratch protection in the Martian sand and dust environment. On the mechanical dimension, material selection needs to be synchronized to crack the mechanical equation and environmental corrosion function: sapphire (single crystal Al₂O₃) becomes the first choice for deep-sea probe observation windows with Mohs 9 hardness and 3.2 GPa compressive strength, and its hemispherical geometric design controls the deformation under 60 MPa hydrostatic pressure to <5 μm through the stress distribution formula σ=Pr/(2t); and the aerospace optics system adopts the CTE ≈ 0.05×10-⁶/°C ULE glass, the interfacial stress of the window-support structure is <10MPa in the temperature change of -150~+100°C by molecular-level CTE matching technology. Facing the multi-environmental attack, modern surface engineering has built a multi-dimensional defense system: plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) of HfO₂/Al ₂O₃ multilayer film can maintain >5 years of protective life in the corrosive liquid of pH=0~14; hydrophobic-antistatic composite coating with bionic compound eye structure (contact angle >160°, surface resistance <1kΩ/sq) enables the UAV photoelectric ball to realize zero droplet adhesion in the tropical rainforest; and the ultra-surface broad-spectrum antireflective layer based on the principle of non-Ermionic photonics (reflectance <0.1% @400- 1600nm) is turning the UAV photoelectric bulb into an anti-reflective layer. 1600nm), pushing the light energy utilization of optical windows to the theoretical limit of 99.9%.

Table 2 Performance Parameters and Adaptation Range

Performance Dimension | Typical values for UV systems | Typical Values for Infrared Systems | Extreme Environment Enhancement Program |

Transmittance | Fused Silica>99%@193nm | CVD-ZnS>70%@10μm | Gradient Refractive Index Coating |

Surface Roughness | 0.2nm RMS(EUV Lithography) | 5nm RMS(LWIR Window) | Plasma Beam Shaping |

Coefficient of Thermal Expansion | 0.5×10⁻⁶/℃(Synthetic Quartz) | 7×10⁻⁶/℃(Ge) | SiC-Sigradient Welding |

Corrosion Resistance | <1nm/Year@pH1-13 | <5nm/Year@ Salt Spray ASTM B117 | Atomic Layer Deposition Al₂O₃ |

Optical Window Sheets of Several Materials

Si Window Sheet

Silicon is suitable for use in the near-infrared band in the 1.2-8 μm region. Because silicon is characterized by low density (its density is half that of germanium or zinc selenide materials), it is particularly suitable for applications where weight requirements are sensitive, especially in the 3-5um band. Silicon has a Knoop hardness of 1150, which is harder than germanium and not as fragile as germanium. However, it is not suitable for transmission applications in CO2 lasers due to its strong absorption band at 9um.

Silicon (Si) single crystal is a chemically inert material that is hard and insoluble in water. It has good light transmission in the 1.2 -7um band, and it also has good light transmission in the far-infrared band of 30-300μm, which is not a characteristic of other infrared materials. Silicon (Si) single crystal is usually used as a substrate for 3 -5μm mid-wave infrared optical windows and optical filters. Because of the material's good thermal conductivity and low density, it is often used in the production of laser mirrors and more sensitive to the weight of the volume of the occasion. Silicon lenses or windows, the use of optical grade silicon single crystal, the diameter range is: 5 ~ 260mm, the surface accuracy is usually up to 40/20, the surface flatness of up to: λ/10 @ 633nm (the ratio of the thickness of the lens to the diameter of the lens to comply with the processing ratio).

Fig. 5 Si Window Sheet

Ge Window Sheet

Germanium materials have a very high refractive index (about 4.0 in the 2-14 μm band), and when used as window glass, they can be coated as needed to increase the transmittance in the corresponding band. Furthermore, the transmittance properties of germanium are extremely sensitive to temperature changes (transmittance decreases with increasing temperature) so they can only be used at temperatures below 100℃. The density of germanium (5.33 g/cm3) is taken into account in the design of systems with stringent weight requirements. Germanium windows have a wide transmission range (2-16 μm) and are opaque in the visible spectral range, making them particularly suitable for infrared laser applications. The Knoop hardness of germanium is 780, roughly twice the hardness of magnesium fluoride, which makes it more suitable for applications in the IR field of variable optics.

Because Ge has a high Nu's hardness, it is often used in infrared systems that require higher intensity, due to its high refractive index, usually we will be plated with a transmittance enhancement film on Ge, commonly used bands are from: 3~12um or 8~12um. the transmittance rate of Ge will decrease with the increase of temperature when it is heated, strictly speaking, the best temperature for the best application of Ge is below 100 degrees Celsius in the environment, when applied in weight-sensitive systems, it is recommended that designers take into account the high-density characteristics of Ge. The ratio of lens size to thickness should be by the processing ratio, and the weight should be by the design requirements. Ge lenses and windows are available in diameters ranging from 5 to 260 mm, with surface accuracies of up to 20/10, and surface flatness of up to λ/10@633 nm (the ratio of lens thickness to diameter should be by the processing ratio).

Fig. 6 Ge Window Sheet

ZnSe Window Sheet

Because ZnSe has a low absorption coefficient and a high thermal expansion coefficient, it is commonly used as a substrate material for mirrors and beam splitters in high-power CO2 laser systems. However, due to the relative softness of ZnSe (120 on the Knoop scale), it is easy to be scratched, so it is not recommended to be used in harsh environments, and it is better to wear finger cots or gloves when holding and cleaning it with even force. the diameter of ZnSe windows or lenses ranges from 5~220mm, and the surface accuracy can be up to 20/10, and the surface flatness can be up to λ/10@633nm (the ratio of the thickness of the lenses to the diameter needs to meet the processing ratio).

Fig. 7 ZnSe Window Sheet

CaF2 Window Sheet

Calcium fluoride has high transmittance from UV to mid-infrared (250nm~7um), so it is widely used in the manufacture of prisms, windows and lenses, etc. In some applications with a wide spectral range, it can be used directly without coating, especially since it has low absorption and high laser threshold, which is very suitable for excimer laser optical systems. Calcium fluoride lenses or windows, diameter range: 5~150mm, surface accuracy usually up to 40/20, surface flatness up to: λ/10@633nm (the ratio of the thickness of the lens to the diameter should be by the processing ratio).

Fig. 8 CaF2 Window Sheet

BaF2 Window Sheet

Barium fluoride crystals have a wide range of transmittance, with good transmittance in the wavelength range of 0.13μm~14μm. TSingle crystals and polycrystals exhibit similar performance; however, producing single crystals is challenging, making them twice as expensive as polycrystals. It can be used for infrared switchboard windows, Fourier gas analysis windows, oil and gas detection, high-power lasers, optical instruments, and so on. In barium fluoride lens or window, the diameter range is: 5~150mm, the surface accuracy is usually up to 40/20, and the surface flatness can be up to: λ/10@633nm (the ratio of the thickness of the lens to the diameter needs to comply with the processing ratio).

Common Applications of Optical Window Sheets

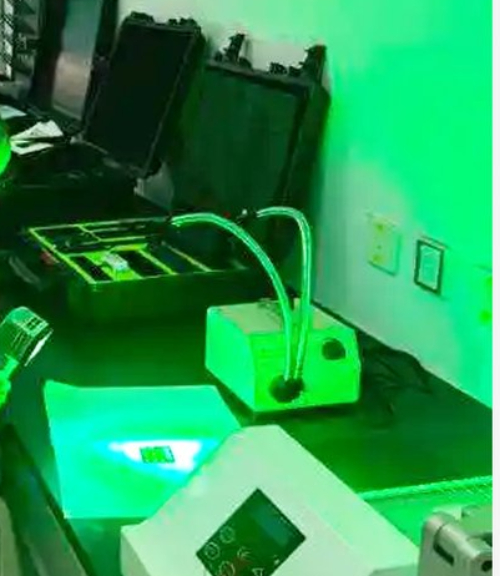

As the “intelligent sensory interface” of the optical system, the optical window sheet shows technical penetration in seven core fields: in the aerospace field, the fused silica window of the Hubble Telescope captures starlight 13 billion light-years away with λ/20 surface accuracy, while the Mars Rover adopts a sapphire-aluminum-titanium composite window that maintains panoramic imaging in the extreme temperature difference of -120°C~+80°C. In the automotive industry, the aluminum nitride window of LIDAR (transmittance >95%@905nm) achieves millimeter-level ranging accuracy at 200Hz scanning frequency through anti-vibration packaging technology. In the automotive industry, LIDAR's aluminum nitride window (transmittance >95%@905nm) achieves millimeter-level ranging accuracy at a scanning frequency of 200Hz through anti-vibration encapsulation technology, while HUD head-up displays rely on wedge-shaped optical resins (refractive index of 1.53±0.002) to eliminate ghosting aberrations; in the medical endoscopy, the magnesium fluoride micro-window with a diameter of only 2.8mm (biocompatibility Class VI) equipped with anti-protein adsorption coating to achieve 4K-class image transmission in the human body cavity; high-energy laser system selects gradient-doped zinc selenide window (damage threshold>5J/cm² @10.6μm), and the thermally induced phase compensation algorithm counteracts the thermal lens effect of kilowatt-class lasers; in the field of consumer electronics, the TOF sensor of smartphones adopts nanoimprinted antireflection window (reflectance<0.3%@850nm), while the smartphone TOF sensor adopts nanoimprinted antireflection window (reflectance<0.3%@850nm). 850nm), while the sapphire touchscreen of smartwatches is strengthened by ion exchange to increase the Mohs hardness to 8.5; in defense security, the optoelectronic masts of armored vehicles are equipped with borosilicate-silicon carbide composite windows that can withstand the impact of 7.62mm armor-piercing bullets (EN1063 BR7 standard), and submarine optoelectronic systems use hemispherical zinc sulfide windows (withstanding pressure of 60MPa) to achieve underwater The submarine optronics system uses hemispherical zinc sulfide windows (60 MPa pressure resistant) to achieve underwater optical reconnaissance at 100 meters. These innovative applications reveal that the optical window has evolved from a passive protective element to an active functional carrier integrating material science, precision optics, and intelligent algorithms, continuously expanding the dimensional boundaries of human perception of the physical world.

Fig. 9 Optical Windows for Testing Instruments

Conclusion

As a key component of the optical system, the material selection and performance design of the optical window are always centered on the comprehensive balance of transmittance, mechanical strength, and environmental adaptability. The material systems represented by fused silica, sapphire, and zinc selenide have achieved precise optical adaptation in the whole wavelength range from ultraviolet (200 nm) to long-wave infrared (14 μm) through crystal structure optimization (e.g., ultraviolet transmittance of high-purity silica), surface coating technology (e.g., anti-reflective and corrosion-resistant plating), and precision machining process (e.g., sub-nanometer-scale surface roughness control). In extreme application scenarios, the in-depth matching of material properties and engineering needs becomes the core: aerospace optical systems rely on fused silica's low coefficient of thermal expansion (0.05×10-⁶/°C), and radiation resistance to guarantee the imaging stability of deep-space probes; medical endoscopes use biocompatible magnesium fluoride windows (by ISO 10993) to maintain 92% of visible light transmittance while avoiding the risk of damage. The medical endoscope adopts a biocompatible magnesium fluoride window (compliant with ISO 10993 standard), which maintains 92% visible light transmittance while avoiding rejection of human tissues; and the high-energy laser suppresses the thermal lens effect through the gradient doping of zinc selenide material (damage threshold>5J/cm²). The current technology system shows that the performance enhancement of optical windows relies on the multidisciplinary synergy of materials science, optical engineering, and precision manufacturing, and its cross-field applications (covering deep space exploration, biomedicine, national defense and security, etc.) not only validate the effectiveness of the existing materials solutions but also provide fundamental support for the reliable operation of optoelectronic systems in complex environments.

Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM) specializes in producing high-performance optical window sheets through advanced material science and precision engineering. We deliver customized solutions that ensure superior optical transmittance, mechanical strength, and environmental resilience for a wide range of applications.

Related Reading: