Toughness, Hardness, and Strength

What Is Toughness

Toughness is a material's ability to absorb energy and plastically deform without fracturing. It is a combination of both strength and ductility, meaning that a tough material can withstand both high stresses and significant deformation before breaking. Toughness is often measured by the area under the stress-strain curve in a material’s tensile test, representing the total energy the material can absorb before failure. It is commonly measured in joules (J) or pound-force inches (lbf·in).

Hardness vs. Toughness

While both hardness and toughness refer to a material’s resistance to deformation, they represent different properties:

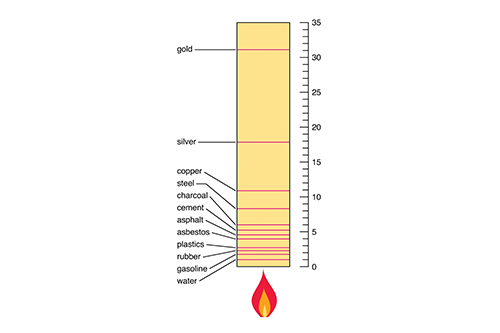

· Hardness is the ability of a material to resist localized plastic deformation, typically from indentation or scratching. Hard materials can resist surface wear and abrasion.

· Toughness, on the other hand, refers to the ability of a material to absorb impact energy and deform plastically without breaking. A tough material is not necessarily hard, and a hard material may not necessarily be tough.

For example, ceramics are often very hard but not tough, as they are brittle and prone to breaking under impact. Metals, such as steel, tend to be tougher than ceramics, meaning they can withstand both force and impact without cracking.

Toughness and Strength

Strength refers to a material’s ability to withstand an applied force without breaking or deforming permanently. Toughness is different from strength in that it measures how much energy the material can absorb during deformation before it fractures. A material can have high strength but low toughness, such as some brittle materials like cast iron, or it can have high toughness and lower strength, like some ductile metals.

For instance:

- Steel: Some types of steel are designed for high strength and toughness, making them suitable for construction and automotive applications.

- Cast Iron: While strong in compression, cast iron is brittle and has low toughness, meaning it is prone to breaking under tension or impact.

Factors Affecting Toughness in Metals

1. Temperature:

- At low temperatures, many metals become brittle and lose toughness, making them more susceptible to fracture. This is why materials used in cold climates, like steel for pipelines or aircraft, are often specifically treated for low-temperature toughness.

- High temperatures can also affect toughness, but materials can become more ductile and less likely to fracture.

2. Grain Structure:

- Materials with fine-grained structures tend to have higher toughness because smaller grains create more obstacles for dislocations (microscopic shifts in the material’s crystal lattice), which helps the material absorb more energy before breaking.

3. Alloying Elements:

- The addition of alloying elements like carbon, nickel, and chromium can enhance a material’s toughness. For example, adding nickel to steel increases its toughness, especially at low temperatures.

4. Heat Treatment:

- Heat treatment processes such as quenching and tempering can improve toughness by adjusting the microstructure of the metal. For instance, tempered martensitic steel has a better balance of toughness and strength than untreated martensite.

5. Strain Rate:

- High strain rates (rapid application of stress) can decrease toughness, making materials more likely to fracture under impact. Materials subjected to slow, gradual stress are generally tougher.

Applications Requiring High Toughness

Materials with high toughness are essential in industries where failure due to impact or stress is catastrophic. Some key applications include:

- Aerospace: Aircraft materials need to withstand high-stress conditions and impact forces without breaking.

- Automotive: Car components such as bumpers, frames, and suspension parts are designed with high toughness to absorb impact energy during accidents.

- Construction: Structural steel used in buildings and bridges must be tough enough to handle dynamic loads, including wind and seismic forces.

- Sports Equipment: Helmets, protective gear, and other sporting equipment are designed for high toughness to absorb impacts and protect the user.

- Military: Armor plating and vehicle structures need high toughness to survive extreme impact forces.

Toughness and Hardness in Common Metals

|

Material |

Toughness (J) |

Hardness (Rockwell C) |

Example Uses |

|

Steel (Carbon Steel) |

High |

40 - 60 |

Construction, automotive, machinery |

|

Stainless Steel |

Moderate to High |

30 - 60 |

Medical instruments, kitchenware, industrial parts |

|

High |

30 - 40 |

Aerospace, medical implants, marine applications |

|

|

Cast Iron |

Low |

30 - 50 |

Engine blocks, pipes, machinery parts |

|

Aluminum |

Moderate |

20 - 30 |

Aircraft, automotive, lightweight structures |

|

Copper |

Moderate |

40 - 50 |

Electrical wiring, plumbing, industrial applications |

|

High |

45 - 60 |

Chemical processing, aerospace, marine engineering |

|

|

Tool Steel |

High |

60 - 65 |

Cutting tools, industrial machinery |

For more information, please check Stanford Advanced Materials (SAM).

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between toughness and ductility?

Ductility is a material's ability to deform under tensile stress, while toughness is its ability to absorb energy and deform without fracturing. Ductility contributes to toughness, but they are not the same property.

Can hardness affect toughness?

Yes, increased hardness often leads to decreased toughness. Hard materials, like ceramics or hardened steel, are more prone to cracking under impact or sudden stresses, making them less tough.

Is high toughness always desirable?

High toughness is essential in applications where materials must withstand impacts or extreme stresses, such as aerospace and automotive industries. However, some applications, like cutting tools, prioritize hardness over toughness.

How does temperature affect toughness?

At low temperatures, most metals become more brittle, reducing their toughness. High temperatures can also affect toughness, depending on the material, making it either more ductile or, in some cases, more prone to softening.

Why is toughness important in construction?

Toughness is crucial in construction because it ensures that materials can absorb dynamic loads and impacts, such as those from earthquakes, wind, or heavy machinery, without failing catastrophically.