Curie Temperature of Permanent Magnets

What Is Curie Temperature

The Curie temperature (or Curie point) is the critical temperature at which a magnetic material loses its permanent magnetic properties and becomes paramagnetic. Named after the physicist Pierre Curie, the Curie temperature represents the transition between ferromagnetism (strong magnetic behavior) and paramagnetism (weak magnetic behavior) in a material.

Above this temperature, the thermal energy disrupts the alignment of the magnetic dipoles, preventing them from maintaining a stable magnetic field. As a result, the material no longer exhibits strong magnetic properties and becomes influenced only by external magnetic fields. Once cooled below the Curie temperature, the material regains its ferromagnetic properties if it is still within the material's stability range.

Factors Affecting Curie Temperature

Several factors influence the Curie temperature of a material. These factors are primarily related to the material's atomic structure and the interactions between magnetic moments. Some key factors include:

1. Material Composition:

The composition of the material, including the elements and their atomic arrangements, has a significant impact on the Curie temperature. For example, iron (Fe) has a Curie temperature of about 770°C, while alloys like neodymium-iron-boron (NdFeB) have higher Curie temperatures, making them more stable at elevated temperatures.

2. Atomic Structure:

The type of atomic bonding and the electron configuration in the material affect the Curie temperature. Materials with strong magnetic exchange interactions, like rare-earth magnets, tend to have higher Curie temperatures compared to those with weaker interactions.

3. Magnetic Anisotropy:

Magnetic anisotropy refers to the directional dependence of a material’s magnetic properties. High anisotropy can increase the Curie temperature as the material can better resist the randomizing effects of thermal energy at higher temperatures.

4. Impurities and Defects:

Impurities and crystal defects can lower the Curie temperature. They introduce irregularities that disrupt the alignment of magnetic moments, reducing the material’s overall magnetic ordering and lowering the temperature at which it loses its magnetization.

5. External Pressure:

Applying pressure can also influence the Curie temperature by altering the atomic spacing and bonding within the material. In some materials, pressure can either raise or lower the Curie temperature, depending on how it affects the exchange interactions.

Curie Temperature vs Max Working Temperature

It is important to distinguish between the Curie temperature and the maximum working temperature of permanent magnets. While both relate to a material's thermal limits, they represent different phenomena:

· Curie Temperature:

This is the temperature at which a permanent magnet loses its permanent magnetization, as explained earlier. Above this temperature, the material becomes paramagnetic, which means it no longer behaves as a magnet without an external field.

· Max Working Temperature:

The maximum working temperature refers to the highest temperature at which a material can be used in a specific application without undergoing degradation in its magnetic properties. Permanent magnets can continue to function at temperatures below their Curie temperature, but their performance may decrease as the temperature approaches this limit. Factors such as reduced magnetic strength, altered coercivity, and thermal expansion may affect the performance of the magnet at elevated temperatures.

Thus, while the Curie temperature marks the loss of permanent magnetism, the maximum working temperature refers to the highest temperature at which a magnet can still perform its intended function with minimal loss in efficiency.

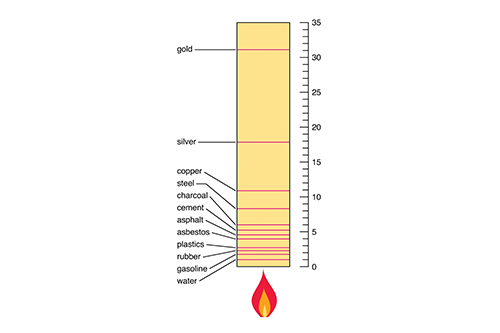

Curie Temperature of Permanent Magnets

The Curie temperature varies significantly across different types of permanent magnets, depending on their material composition and structure. Here is a comparison of the Curie temperatures for some commonly used permanent magnets:

|

Magnet Type |

Curie Temperature (°C) |

|

~770 |

|

|

Nickel (Ni) |

~358 |

|

Cobalt (Co) |

~1,115 |

|

~1,300 to 1,400 |

|

|

Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) |

~310 to 400 |

|

Alnico |

~850 to 1,200 |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Curie temperature?

The Curie temperature is the temperature at which a magnetic material loses its permanent magnetism and becomes paramagnetic. This transition occurs when thermal energy disrupts the alignment of magnetic moments in the material.

How is the Curie temperature determined?

The Curie temperature is typically determined experimentally by measuring the magnetic properties of a material as it is heated. The temperature at which a significant decrease in magnetization is observed indicates the Curie temperature.

Does the Curie temperature vary for all materials?

Yes, the Curie temperature varies significantly across different materials depending on their atomic structure, composition, and magnetic interactions. For instance, rare-earth magnets have higher Curie temperatures compared to common materials like iron.

How does the Curie temperature affect the performance of a magnet?

Once a material exceeds its Curie temperature, it loses its permanent magnetic properties and can no longer act as a stable magnet. This can lead to a loss of function in applications that rely on the material’s magnetic properties.

What is the maximum working temperature of a magnet?

The maximum working temperature is the highest temperature at which a magnet can operate without significant loss of performance. It is generally lower than the Curie temperature, and performance can degrade as the temperature approaches this limit.